And What the DND Case Teaches Us About Governance, Agents, and Strand Commonality

By Jon W. Hansen | Procurement Insights

A recent discussion sparked by Michael Lamoureux’s post “Outcomes Is a Dirty Word” quickly drew in familiar voices: Pierre Mitchell, Jason Busch, Joël Collin-Demers, Phil Fersht, Philip Ideson — and, in a parallel thread, Vera Rozanova, Marcel Van Wonderen, and Arne Jonas Schmidt.

At first glance, these looked like separate conversations. One about whether “outcomes” pricing makes sense. Another about why procurement transformation keeps stalling despite better tools. Another about fear, excuses, and hiding behind process.

They are not separate conversations.

They are different descriptions of the same systemic failure.

And the reason they never quite converge is because they are missing one thing: agent-based governance and Strand Commonality (shared meaning and accountability across agents and metrics) across the extended Metaprise (the full network of internal functions and external partners that must move together for transformation to succeed).

The Positions (in Their Own Words)

Philip Ideson: “Outcomes are fine if you are able to tolerate the behaviors that your outcomes incentivize.” This is a behavioral statement. Outcomes create incentives. Incentives create behavior. Behavior creates real results — good or bad.

Pierre Mitchell: Outcomes are lagging indicators. Capabilities and competencies are leading indicators. Strategy is about building the right capabilities.

Jason Busch: We need auditability, traceability, chain-of-thought, and technical systems that can log and explain decisions.

Joël Collin-Demers: Most “outcome-based” models are really usage-based pricing with better branding.

Phil Fersht: Outcomes only matter when baselines are transparent, levers are controllable, and value remains after the vendor leaves.

Meanwhile, in a parallel discussion:

Vera Rozanova: Technology advances faster than social structures. Humans are brilliant but constrained by fear and short-term thinking.

Marcel Van Wonderen: We can predict risk and automate the obvious, yet when a real decision appears, we hide behind process, policy, and PowerPoint.

Arne Jonas Schmidt: Sad, but true.

These are not contradictions. They are fragments of a larger truth.

Measuring outcomes without modeling agent behavior and incentive conflict is like measuring symptoms without diagnosing the disease.

The DND Case: When “Outcomes” Collide

The Department of National Defence case from the Procurement Insights archives illustrates the problem in documented, empirical terms.

The service department defined its primary outcome as: “More service calls completed per day.”

To achieve this, technicians delayed ordering parts until late afternoon so they could keep moving from call to call, maximizing their personal performance metric. Service calls per day went up. From their perspective, they were succeeding.

But downstream, procurement outcomes collapsed: rush orders drove prices higher, delivery performance deteriorated, compliance dropped.

And ironically, service outcomes collapsed too: calls could not be resolved because parts arrived late, rework increased, customer satisfaction dropped.

So which outcome was “right”?

The service department optimized one outcome. Procurement paid the price. The enterprise lost.

This is what happens when outcomes are defined locally, without governance across agents.

Where Each Comment Fits in the DND Example

Philip’s point becomes empirical fact: “Are you able to tolerate the behaviors your outcomes incentivize?” DND tolerated them — until the system broke.

Pierre’s point is also correct. Capabilities matter. But the missing capability was not technology. It was governance capability: the ability to harmonize definitions and incentives across functions.

Jason’s point is partially correct. You could log every action the technicians took. You could audit every order time. But without governance, you would simply get perfect records of the same failure repeating itself.

Joël is right about branding. Outcome-based pricing layered on top of misaligned incentives just monetizes dysfunction.

Phil Fersht is right. Without controllable levers and durable value, “outcomes” are marketing, not transformation.

And Vera and Marcel explain why this persists. Because humans default to comfort, fear, and process when accountability is unclear.

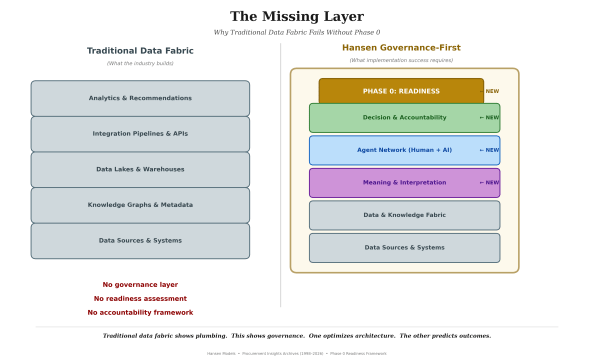

The Missing Layer: Agent-Based Governance

All of these perspectives point to the same missing layer.

Outcomes emerge from interacting agents with competing incentives. Without agent-based modeling, each function defines success differently, each optimizes its own metric, and no one owns the system-level result. Procurement, service, finance, suppliers, and leadership are not separate systems. They are interdependent agents across the extended Metaprise. And unless their outcome definitions share Strand Commonality — aligned meaning, aligned accountability — one agent hits its target, another misses, and the organization loses.

Governance Is Not Rules. It Is Harmonization.

This is the critical correction.

Governance is not bureaucracy. It is not policy manuals. It is not process theater.

Governance is the collective insight that harmonizes outcomes across agents.

It answers: Who decides? Whose outcome takes priority when metrics conflict? What behavior is rewarded? What behavior is unacceptable? What trade-offs are explicit and owned?

Without this layer, outcomes are lagging indicators of chaos, capabilities exist in silos, and technology accelerates fragmentation.

Why the Outcomes Debate Never Resolves

The debate keeps circling because everyone is right — but incomplete.

Outcomes are lagging indicators (Pierre). Behaviors matter (Philip). Auditability helps (Jason). Pricing models are abused (Joël). Leadership must choose accountability (Vera, Marcel).

What is missing is the unifying model: agent-based governance that reveals where outcomes conflict, why they conflict, and how to realign incentives so the system moves together. That is Strand Commonality. That is what Phase 0 measures before technology selection begins.

The Real Question

The real question is not: Should we measure outcomes?

The real question is: Do we understand the behaviors and agents that produce those outcomes?

Because without that, outcomes become slogans, KPIs become weapons, and transformation becomes theater.

The DND case did not fail because of bad tools. It failed because of misaligned outcome definitions across agents. And that is exactly what we are still doing today — just with better technology.

Closing Thought

Vera was right: technology advances faster than social structures. Marcel was right: we hide behind process when real decisions appear. Philip was right: outcomes reveal the behaviors we tolerate. Pierre was right: capabilities matter. Jason was right: traceability matters. Joël was right: branding hides reality.

But without agent-based governance and Strand Commonality, all of these truths remain isolated.

Outcomes don’t need better measurement. They need better meaning.

That is the governance gap.

The DND Video

The Department of National Defence case referenced in this post is documented in full here. This is not theory. This is what happens when outcomes are defined locally without governance across agents — and what changes when you measure readiness first.

Watch: The DND Case — Agent-Based Governance in Practice

-30-

Tim Cummins

February 3, 2026

It should be obvious that outcomes matter and our research has identified multiple examples of success. However, it’s notable that procurement is rarely involved. The debate you reference perhaps explains why!

piblogger

February 3, 2026

Tim — thank you. That’s exactly the point I was trying to surface. Outcomes do matter, but they don’t exist in isolation — they’re the product of decision rights, incentives, and accountability across functions. When procurement isn’t involved early, “outcomes” get defined locally (or contractually) without system-level harmonization, and the enterprise ends up optimizing competing targets. That’s the governance gap — and why Phase 0 readiness has to come before measurement, automation, or outcome-based promises.